Fred Brooks’s classic book The Mythical Man-Month was published 50 years ago. It was hugely influential on the then-nascent discipline of software development. How does it stand up today?

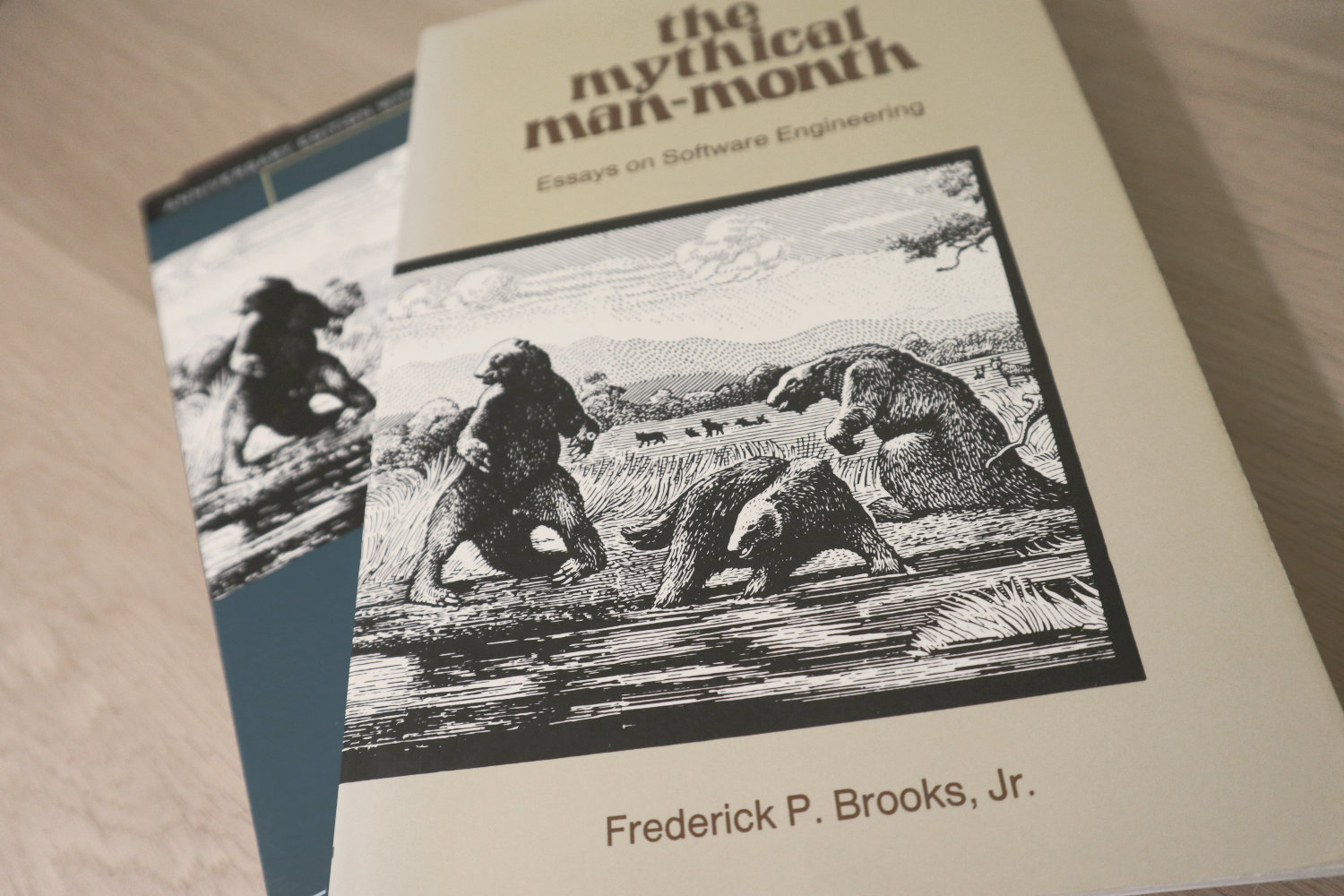

Frederick P Brooks Jr’s classic book The Mythical Man-Month: Essays on Software Engineering was published in 1975 – 50 years ago. The book introduced many ideas and principles that were hugely influential on early practitioners of our craft. But which ideas have withstood half a century of technological change, and which have not?

I got myself a copy of the original 1975 edition and the extended 20th anniversary edition, which added four new chapters. Here are my thoughts, organized by the main themes of the book and roughly aligning with the order of the chapters.

The tar pit

The Mythical Man-Month is more of an anthology of standalone essays rather than a cohesive thesis. Nevertheless, there are some key themes that run throughout. The most prominent theme is the one introduced in the opening chapter: that the core challenge of software development is the management of complexity.

Brooks draws the colorful analogy that large-scale software development is like “the mortal struggles of great beasts in the tar pits”. This is represented by the book’s cover image, a sketch of Charles Knight’s 1925 painting that depicts the great mammoths of the Pleistocene struggling to free themselves from the tar pits of Southern California.

“Large and small, massive and wiry, team after team has become entangled in the tar,” Brooks writes. His thesis is that it is never one problem, but rather a combination of intractable problems, some unexpected, that make it difficult to move complex projects forward. “No one thing seems to cause the difficulty – any particular paw can be pulled away. But the accumulation of simultaneous and interacting factors brings slower and slower motion.”

Despite the immense technological advances of the past half-century – in computer hardware, in programming languages and runtime environments, and in tools and automation that support every aspect of software delivery – the core challenge of software development remains the management of complexity.

OS/360

Throughout the book, Brooks draws on his own experiences, notably as the manager who oversaw the initial design of IBM’s OS/360 operating system. At the time, OS/360 was one of the biggest, most ambitious, most complex software projects ever attempted. At the peak of the project, more than a thousand people worked on it.

But, as Brooks acknowledges, the project was not “wholly successful”. The initial release of OS/360, in 1966, was delivered “late, it [used] more memory than planned, the costs were several times the estimate, and [the first version] did not perform very well”.

The opening chapter serves as Brooks’s post-mortem of the OS/360 project. He concludes that the fundamental reason for the project’s difficulties was that the overall costs of delivering such a large-scale software system had been massively underestimated from the start. This happened because the estimates were based solely on the construction of the individual parts of the system. What had not been accounted for was the integration costs of all those components, and the “productization” of the whole solution.

Brooks estimates that the work of designing the interfaces between all the components of a system, coordinating their integration, and incrementally extending integration tests, has the potential to triple the initial cost of coding all the components in isolation. Costs may triple again for all the work that goes into preparing a large-scale software system for distribution as shrink-wrapped software for general use by the public. For the OS/360 project, they had not fully accounted for how much extra rework and testing would be needed to make the system run reliably in “many operating environments, for many sets of data”, and for time spent preparing user-facing documentation and other packaging.

Brooks estimates that, in total, building large, general-purpose, shrink-wrapped software products can cost up to nine times (3x3) more than writing all the code as separate, non-integrated, private libraries.

In other words, programming effort is a small proportion of the overall cost of a large-scale software project.

This analysis stands up well today. It is widely understood that the production of computer program code is just a small part of the overall cost of building large-scale commercial software products.

The mythical man-month

The eponymous second chapter builds on the thesis of the first chapter. It deals with the perennial issue of software projects being notorious for going over budget, being delivered later than estimated, else failing to meet expectations in functionality and performance.

Based on his experience on OS/360, Brooks suggests that the costs of large-scale software projects typically break down into approximately one-third for design, one-sixth for coding, and half for debugging and testing – split roughly equally between component testing (ie. unit and integration testing) and system (end-to-end) testing. Unfortunately, Brooks concludes, you cannot estimate the cost of a software project simply by working out the programming effort and then multiplying for the other cost factors. “The coding is only one-sixth or so of the problem, and errors in its estimate or in the ratios could lead to ridiculous results.”

The consequence of basing costs and schedules on programming effort alone is that, if schedules are not subsequently adjusted to accommodate all the other necessary work, then quality is necessarily compromised to meet the original schedule. Most lamentably of all, such plans leave no room for product refinement based on real-world product testing.

Project after project designs a set of algorithms and then plunges into construction of customer-deliverable software on a schedule that demands delivery of the first thing built.

Drawing on research from the era, Brooks shows that programming effort increases as a power of the size and complexity of the computer program under development. Brooks estimates that the cost of coding a small program will be only about one-fourth of the cost of coding a larger program twice the size. Programming productivity varies by category of software, too, such as operating systems versus compilers, suggesting that complexity is as much a factor as size.

In my experience, we still have a tendency to estimate software development costs based primarily on the coding of individual modules, rather than considering the integration of those modules into a cohesive system, the size and complexity of the whole product, and the work that goes into making a software product ready for end users – just as the project managers had failed to do for OS/360 over 50 years ago.

Besides the problems encountered on the OS/360 project, Brooks considers numerous other explanations for why estimating and scheduling of software projects is so error-prone.

Optimism

The first explanation the author gives for poor project estimation is a bias toward optimism.

Brooks writes that “all programmers are optimists”. He hypothesizes that, because the age distribution of programmers in 1975 was skewed toward younger age groups, and because younger people tend to be more optimistic than the population at large, then software project estimates are particularly vulnerable to being wildly optimistic.

I’m not wholly convinced by this argument. Sure, younger developers lack the necessary experience to do accurate estimates. But I’ve found senior developers to be just as guilty of optimism bias. Contingency planning and risk management are still poorly practiced in many software projects today – regardless of who’s drawing up the project plans.

Brooks adds that the very notion that the development of complex software systems can be accurately estimated is flawed. He writes that “the programmer builds from pure thought-stuff” and that “for the human makers of things, the incompleteness and inconsistencies of our ideas become clear only during implementation. Thus it is that writing, experimentation, 'working out' are essential disciplines for the theoretician.”

Brooks reflects that large-scale software development, like OS/360, is inherently hard. The reality of developing commercial software for a living, Brooks writes, is that there are many “dreary hours of tedious, painstaking labor”, often involving analyzing code written by other people who are no longer involved in the project.

This I find to be a more convincing argument. Software development is an inherently complex and unpredictable activity. In every software project, even those with stable and known requirements, there will always be some requirements that are emergent. Requirements may emerge only at the time of construction, or even later, when working software is finally put into the hands of real users. This is the nature of software development, which is more of a design problem than a construction task.

I have long held the view that the very notion that the development of software can be perfectly planned and accurately estimated is deeply flawed. Yet in 2025, as in 1975, the belief that the delivery of complex software can be planned in meticulous detail, and costs controlled accordingly, is still widely held throughout our industry.

Misplaced optimism in big design up-front remains a common cause of cost overruns today.

Progress is not always correlated with effort

The second explanation that Brooks provides for poor estimation is the assumption that delivery schedules can be shortened by adding more programmers. Famously, Brooks writes that “adding manpower to a late software project makes it later.” – a quote that will forever be known as Brooks’s Law.

Brooks’s central argument for this is that adding people to a late project increases total effort. There’s extra effort involved in reorganizing the project delivery plan and managing the larger team. Meanwhile, in-flight work streams are disrupted by the “repartitioning” of work. There follows a permanent increase in intercommunication, required to coordinate the development of dependencies and interfaces, and to manage the integration testing. There’s also more time spent training and onboarding new people.

And some programming tasks just cannot be parallelized, but must be done sequentially. If programmers are already optimally allocated to these tasks, adding more programmers will not speed up their completion. To illustrate this point, Brooks offers the suitably colorful analogy of child bearing:

The bearing of a child takes nine months, no matter how many women are assigned.

Brooks coins the term “man-month” to represent one unit of additional manpower (one person working for one month). Because adding resources to a project in the form of extra man-months increases overall effort, it does not necessarily correspond to an increase in the speed of progress. And yet, 50 years ago, Brooks says this was a widely held belief and a common practice – hence the “mythical” nature of extra man-month resources.

Men and months are interchangeable commodities only when a task can be partitioned among many workers with no communication among them. This is true of reaping wheat or picking cotton; it is not even approximately true of systems programming.

The consequence of this for project management is that, once a schedule is proven to be unrealistic, there may not be anything that can be done to put the project back on track.

The graph below, adapted from the book, shows that software projects have an optimal division of labour, where delivery speed is maximized by optimal allocation of resources. Up to a point, you can reduce your delivery schedule by adding more people to your project. But because adding more people will decrease the productivity of individual team members, there comes a tipping point where this decrease in productivity more than offsets the overall addition of resources – so delivery speed slows despite the extra manpower.

Brooks observes that the more complex the interrelationships between the component parts of the system under construction, the greater this effect. Hence the management of complexity is identified as the core challenge of software development. The simpler the design, the more opportunities you will have to build out the solution faster.

Even today, managers routinely believe that adding more people to a late project can solve schedule slippage. I’ve seen this myself. It’s especially commonplace in consultancies and outsourcing firms, where the supplier bills its customers in man-hours and therefore has a commercial incentive to add as many people as possible to their billable workstreams. But I’ve seen it in software houses, too. They ought to know better.

Regenerative schedule disaster

The third explanation that Brooks provides for poor estimation is what he terms “regressive schedule disaster”.

Brooks writes that project progress tends to be poorly monitored, so when it becomes apparent that schedules have slipped, it’s usually already too late to do anything about it.

In this situation, Brooks says the only recourse is to reschedule the work with the original team members, “un-augmented” by new recruits. This has the effect of delaying completion of the project, but at least overall costs do not needlessly increase through spend on additional staff who will ultimately be under-utilized.

Better to increase the number of months than the number of men – although, of course, this is not the natural instinct of most project managers.

Brooks expands on this subject in chapter 14, titled “Hatching a Catastrophe”, in which he argues for the use of tools like PERT charts, and scheduling techniques like delivery milestones, to keep track of progress. Without good tools and techniques to monitor progress, day-to-day schedule slippage is hard to recognize, hard to prevent, and hard to make up for – leading, imperceptibly, to catastrophically late delivery.

How does a project get to be a year late?… One day at a time.

System testing must be done last

The fourth explanation that Brooks gives for poor estimation is that system testing and debugging must be done last, due to the sequential nature of the work. Consequently, testing “is usually the most mis-scheduled part of programming” and multiple rounds of testing and debugging can end up accounting for as much as half of the overall development schedule.

Brooks expands on this in chapter 13, titled “The Whole and the Parts”, which is about that last step of integrating and testing a complete system, made from its pre-fabricated, pre-tested component parts.

Of course, in the intervening years, our industry has universally adopted iterative and incremental development practices. Best practice now is to deliver small chunks of work, fully integrated into and tested within the evolving product, at regular intervals. In effect, testing and debugging is now done in parallel to design and construction, not sequentially afterward, as it was in the past.

Rather than testing being left until a final deliverable system is complete, the correctness of the evolving system is continuously evaluated throughout its development life cycle. Through this process of continuous integration and testing, we’ve solved the problem of defects in design and construction being discovered late.

Brooks acknowledges this himself. In a retrospective chapter in the 20th anniversary edition of The Mythical Man-Month, Brooks accepts that iterative and incremental development methodologies had, in the intervening years, proven to be more effective than traditional stepwise approaches. Indeed, in his other famous work, No Silver Bullet, a paper published in 1986, just a decade after The Mythical Man-Month, Brooks advocates “growing” software organically through incremental development.

Gutless estimating

The fifth and final explanation that Brooks gives for poor estimation of software projects is the tendency we have to work to schedules dictated by our customers. What we ought to do, Brooks proposes, is to be braver and attempt to make a reasonable guess about the real effort required to deliver a satisfactory product.

Brooks uses the analogy of cooking an omelette. It typically takes a couple of minutes to cook an omelette. But if, after two minutes, the omelette is not set, the customer has two choices: wait, or eat the omelette raw. The chef has a third choice: turn up the heat. But the effect would be to serve a poor quality product – burnt on the outside, and perhaps still raw in the centre.

Good cooking takes time. If you are made to wait, it is to serve you better, and to please you.

– From a menu of a New Orleans restaurant

In the delivery of commercial software, we have a tendency to take the third option: to turn up the heat and try to deliver products within the schedules desired by our customers. “False scheduling to match the patron’s desired date is much more common in our discipline than elsewhere in engineering,” Brooks observes.

Brooks contends we should instead have the “courteous stubbornness” of a chef who refuses to serve a dish until it is ready. Construction of good software, like cooking, takes time. Some tasks just cannot be hurried without spoiling the result.

Brooks suggests that the underlying reason for such widespread “gutless estimating” in our industry is that we do not have mature models for estimating software work. “It is very difficult,” he writes, “to make a vigorous, plausible, and job-risking defense of an estimate that is derived by no quantitative method, supported by little data, and certified chiefly by the hunches of the managers.”

50 years later, there remains a lack of maturity in the methods and tools we use for estimation. Use of abstract proxy measures, like T-shirt sizes and story points, rather than more quantitative data-driven estimation techniques, is commonplace.

The surgical team

In the third chapter, Brooks pitches his solution to the problems of large-scale software development: the surgical team.

The roots of this idea lie in the observation that having a small number of very skilled programmers on a team often proves to be more effective than having a large number of average ones.

Brooks quotes a now-infamous 1968 paper by Sackman et al that postulated that very good programmers can be up to ten times as productive as poor ones.

These studies revealed large individual differences between high and low performers, often by an order of magnitude. It is apparent from the spread of data that very substantial savings can be effected by successfully detecting low performers.

– Sackman et al

This paper is the origin of the idea of the 10x programmer. However, the paper’s findings were debunked by subsequent research. The 1968 study tested programmers on tasks that did not represent real-world programming problems. Neither did the study account for the impact of collaboration, which we now know to be more important than individual capability.

But, at the time, the quantitative analysis provided by the Sackman paper reinforced qualitative observations made by Brooks and other project managers that small “sharp” teams are better than large blunt ones. Better for software development teams to be composed of a small number of “first-class” programmers rather than many mediocre ones.

It is why, Brooks concludes, there are many accounts of two programmers working in a garage to build “an important program that surpasses the best efforts of large teams”. (The cliché of the garage startup has deeper roots than I realized!)

Brooks reiterates his earlier point that throwing lots of man-months at a project can actually slow down delivery. He writes, “the brute-force approach is costly, slow, inefficient, and produces systems that are not conceptually integrated.”

But the problem with small teams is they are too small for really big problems. Brooks notes there were over 1,000 people working on OS/360 at the peak of that project, and a smaller 200-strong team would have taken 25 years to deliver the same product. For large-scale software projects, the delivery timescales achievable by small teams are just not commercially viable.

If we want to prioritize development efficiency and the quality of the final product, we should have small teams of highly skilled, experienced practitioners doing the design and construction. But to deliver large systems in a timely manner, we need very large teams. How can we reconcile these two constraints?

Brooks draws on a solution first proposed by Harlan Mills in a 1971 IBM paper.

Mills proposes that each segment of a large job be tackled by a team, but that the team be organized like a surgical team rather than a hog-butchering team. That is, instead of each member cutting away on the problem, one does the cutting and the others give him every support that will enhance his effectiveness and productivity.

The idea is there would be, not one giant team, but multiple smaller and independent teams. The overall solution is designed as a series of small subsystems, with each subsystem designed and built by one of the teams.

Each team operates similarly to a surgical team in a hospital. Each has a chief programmer, the surgeon, who is in charge of the team’s subsystem. The rest of the team members try to help him complete the project (the surgery).

The chief programmer is responsible for defining and maintaining the conceptual integrity of his team’s part of the overall solution. “He personally defines the functional and performance specifications, designs the program, codes it, tests it, and writes its documentation”. The chief programmer is supported by a copilot who researches design options for the chief programmer to consider, drawing upon the experience and expertise of the rest of the team. The idea is that “few minds are involved in design and construction, yet many hands are brought to bear”.

The chief programmers across all the teams collaborate with each other to coordinate the integrations between the subsystems for which they are each responsible. By structuring an organization as a hierarchy of delivery teams like this, overall communication overhead is minimized. You need only to coordinate the work of the chief programmers, who represent a small portion of the overall number of technicians. Large-scale projects are thus more efficient and more scalable.

Mills named this team structure the chief programmer team. Brooks rechristened it the surgical team.

Although the concept of the surgical team will be unfamiliar to most software developers today, the underlying principles are well understood. The responsibilities of the chief programmer are today split between roles like Technical Lead and Solution Architect. The concept of having a chief programmer supported by a copilot today manifests itself in the pair programming methodology (and, more recently, in AI-augmented programming). And surgical teams as a whole are conceptually similar to the practice of mob programming.

Harlan Mills' work, which was popularized by Brooks in The Mythical Man-Month, laid the groundwork for the software development best practices that were to emerge over the subsequent decades.

Of course, some of the details of the original surgical team design are no longer relevant. Besides the chief programmer and copilot, the original surgical teams also had:

- an administrator to “handle money, people, space, and machines”;

- a technical editor responsible for maintaining documentation;

- a “program clerk” responsible for “maintaining all the technical records of the team in a programming-product library”;

- a “toolsmith” who implements any special tools needed by the team, such as for “file-editing, text-editing, and interactive debugging”;

- a “language lawyer”, someone who is an expert in the programming language and operating system, and who provides consultancy to the team in how best to use them;

- and a tester, responsible for preparing suitable test cases from the functional specifications, and devising dummy data for day-to-day debugging.

Oh, and the administrator and editor would each have their own personal secretaries. Different world!

Today, most roles of the surgical team have been automated away or absorbed into the broad responsibilities of programmers and testers. Every team member now works at the coalface, with no supporting roles. In the old surgical team model, only the chief programmer – or, when they were not available, their copilot – actually wrote any computer code.

But the truth is the surgical team design wasn’t so much about improving communication as it was about dealing with the practical constraints of the era. Memory and disk access were too limited and expensive to be shared by everyone at once. Today there are no such constraints.

As for the myth of the 10x programmer, this remains a regrettable legacy of some of the ideas that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s. Today, the software industry still has an unfortunate habit of glorifying “rockstar” developers and undervaluing teamwork and soft skills.

Conceptual integrity

Brooks is perhaps most famous for his invention of the idea of conceptual integrity.

The dominant theme throughout The Mythical Man-Month is the question of how best to manage complexity in large-scale software systems. Maintaining conceptual integrity, Brooks argues, is the best way of containing complexity as a codebase sprawls.

Conceptual integrity is a quality of a system that emerges from its high-level design. A system with high conceptual integrity is one where all its concepts, and their relationships with each other, are applied in a consistent way throughout. A consistent design philosophy flows through all subsystems. Anywhere you look in the codebase, it demonstrates the same balance of competing forces.

A conceptually well-integrated system tends to be faster to build and test, easier to maintain, and it is less susceptible to bugs and other types of defect. We can also more confidently change parts of such systems, because we can draw upon our mental map of the architecture and understand intuitively the full repercussions of making our changes.

I will contend that conceptual integrity is the most important consideration in system design. It is better to have a system omit certain anomalous features and improvements, but to reflect one set of ideas, than to have one that contains many good but independent and uncoordinated ideas.

I think few modern architects would dispute Brooks’s notion that conceptual integrity is one of the most important principles of software design, though today we are more likely to use terms like “cohesion” and “consistency” to refer to the same qualities.

The difficult is in achieving it. For a system to have high conceptual integrity, Brooks says “the entire system… requires a system architect to design it all, from the top down”. This is difficult to do in large-scale software projects because of the division of labour. The implementation is necessarily broken up into lots of small pieces, each designed and constructed independently by different programmers, who each make different choices and trade-offs.

Brooks draws a parallel with European cathedrals, most of which “show differences in plan or architectural style between parts built in different generations by different builders”. In software, Brooks notes, such conceptual disunity arises not from the passage of time – hundreds of years separating phases of functional extension – but from the decomposition of the design into “many tasks done by many men”.

The solution offered by Brooks is to have one system architect who designs the whole system from top-to-bottom. Multiple surgical teams are overseen by a chief architect, so that the “design … proceed[s] from one mind, or from a very small number of agreeing resonated minds”.

In Brooks’s development model, design and implementation are two distinct phases. First, a system architect defines the interface to the system, then the builders arrive and define the internal implementation. “The separation of architectural effort from implementation is a very powerful way of getting conceptual integrity on very large projects.”

Besides maintaining conceptual integrity, the horizontal division of labour between architecture and implementation also has the happy side-effect of simplifying communication flows within teams.

Top-down versus bottom-up design

Today, we know this development model as top-down design. You start with a clear understanding of the user interface, the overall architectural style that you want to achieve, and the architectural patterns that you want to use. Within that overall design framework, the solution is broken down into a hierarchy of smaller, more manageable subsystems, modules, and components – each initially designed as a black box (only their interfaces are specified, not their internal workings). Each component is then incrementally refined, internal workings designed in greater and greater detail. Additional levels of dependencies and interactions are added incrementally, until the complete system is fully specified.

Top-down design was promoted in the 1970s by IBM researchers Harlan Mills and Niklaus Wirth. Mills had implemented this method with success in a project for the New York Times, leading to the approach being adopted throughout IBM and then the wider IT industry. Wirth, the creator of the Pascal programming language, also advocated for top-down design in his work. He authored an influential paper in 1971 that outlined a three-step design process, a sequence of “stepwise refinements”, that today we would recognize as a top-down design strategy.

The work of Mills and Wirth was influential on Brooks’s own approach to software design. He concluded:

I am persuaded that top-down design is the most important new programming formulation of the decade.

Top-down design methods were favored in software development until the late 1980s. Ever since, bottom-up design has been more highly regarded. Bottom-up design emphasizes building a system from small, primitive components, gradually integrating lots of small parts to compose the complete solution. Top-down design has come to be associated with big design up-front and waterfall methodologies, which are considered old-fashioned and inflexible, while bottom-up design is associated with lean and agile methodologies, which are considered more modern and flexible.

In practice, all software projects combine elements of both top-down and bottom-up design. Only the relative weighting of the two approaches varies from project to project. Mature software development practices do not view either approach as fundamentally superior but instead see them as mutually beneficial. Good software design is about finding a reasonable balance of the two approaches.

Autocracy versus democracy

In the debate over the merits of top-down versus bottom-up design, Brooks draw parallels in the trade-offs between autocracy and democracy. He acknowledges that his proposed top-down approach to software architecture means that the architects behave something of like aristocracy within the technical domain, and that the demographic ideals that help to form cohesive, engaged teams are sacrificed.

“Are not the architects a new aristocracy, an intellectual elite, set up to tell the poor dumb implementers what to do?” Brooks asks himself. “Won’t one get a better product by getting the good ideas from all the team, following a demographic philosophy…?”

Brooks concludes that a reasonable balance must be found between demographic and autocratic approaches. Everyone should be able to contribute ideas, but ultimately there must be a single authority who makes the final decisions.

Both architects and implementers have important roles to play in system design, Brooks writes. Architects, who design the external specification (ie. the user interface), will have a disproportionate influence over the ease of use of the product. On the other hand, the compound effect of all the many low-level design choices made by the programmers along the way will determine the eventual real-world performance of the product.

Brooks also makes the point that implementation – the raw coding – is also a form of creative work, just one that operates at a different level of abstraction to the architecture. “The opportunity to be creative and inventive in implementation is not significantly diminished by working within a given external specification.”

Brooks observes that, unlike other engineering disciplines, in software engineering the phases of design and construction can overlap. The pace is quicker between design and construction in software, compared to other engineering disciplines. The tasks of specification and construction can therefore blend together. Builders can even start their work before the requirements are finalized, as code is easier to change than bricks and mortar.

Today, it is widely recognized that successful delivery of software requires architects and programmers to work closely together. While ivory tower architecture has been resoundingly rejected, there remains a need for some degree of architectural oversight. Programmers have a tendency to take a bottom-up approach to software construction, as their day-to-day work demands they focus on the design of individual features rather than of the overall system. For this reason, maintaining conceptual integrity is often overlooked by programmers working at the coalface. We therefore need architects, taking a more top-down view, to fight complexity by “the disciplined exercise of frills of function, and flights of technique”, and to maintain conceptual integrity in the evolving system design by counteracting the natural force of entropy.

The second-system effect

Continuing the theme of the previous chapter, Brooks calls for “thoroughgoing, careful, and sympathetic communication between architect and builder”. Brooks calls architecture an “interactive discipline”. While he has argued for a clear separation between the roles of architect and builder, he does not mean that the two groups should work in isolation.

The division of work between architecture and implementation must be treated as a two-way conversation, Brooks writes. Early and continuous communication can give the architect good readings on cost, and open a dialog with the programmers on alternative (cheaper) implementations. Early and continuous communication also instills confidence in the design in the builders.

Architects should suggest, not dictate, implementation strategies, he writes. The builders, ultimately, have responsibility for the implementation, but they might also suggest changes to the architecture. The architect must deal “quietly and privately” with ideas put forward by the builders – perhaps “some minor feature may have unexpectedly large costs when the implementation is worked out”.

This collaborative approach requires what we would today label emotional intelligence and psychological safety. Soft skills, such as empathy and communication, are today widely recognized as essential for high-performing teams, even more so than hard technical expertise.

Brooks then moves on to the main topic of this fifth chapter, which he calls the second-system effect. This is the idea that "version 1" of a new software system is often the best version, because it is simple and elegant. But the "second system" (ie. a later major version) tends to be over-engineered and bloated with features.

“The general tendency is to over-design the second system, using all the ideas and frills that were cautiously sidetracked on the first one.” The result is a “big pile”. Brooks gives the example of the IBM 709, an upgrade to the IBM 704. While the 704 was “very successful and clean”, the 709’s “operation set [was] so rich and profuse that only about half of it was regularly used”.

To counteract the second-system effect, Brooks writes that architects must practice self-discipline “to avoid functional ornamentation and to avoid extrapolation of functions that are obviated by changes in assumptions and purposes”.

In 2025, the second-system effect is alive and well. All continuously-developed software systems suffer from entropy. The worst ones eventually collapse under their own weight of complexity and ambition.

As a way to counteract the second-system effect, Brooks proposes that architects should assign a value to “each little function”: “capability x is worth not more than m bytes of memory and n microseconds per invocation”, for example. Translating such benchmarks from system programming to modern application programming will require use of different metrics, but the principle remains a sound one. Perhaps if we applied technical constraints to each feature like this, our software products might remain leaner and more focused for longer.

But it is perhaps more common today to incorporate refactoring into maintenance activities, else to make code so cheap to produce that we are happy to rebuild our applications from scratch every few years – as Google famously does.

Pilot systems

In chapter 11, titled “Plan to Throw One Away”, Brooks proposes building pilot systems as an intermediate step between the initial system design and the construction of the final product.

A pilot system, which is intended to be cheaply produced and disposable, helps to identify problems with a design before costs are incurred building the final production-grade product.

The idea is taken from chemical engineering, where a new production process is rarely taken straight from the lab to the factory in a single step. More typically, a pilot plant is built to give experience in scaling up production of the final product.

Brooks uses the analogy of letter writing, suggesting that successful software development depends a great deal on trial and error. The pilot system allows the process of trial and error to be played out in a throw-away “draft” system, which he argues is preferable to incrementally changing the production system mid-flight.

Plan to throw one away; you will, anyhow.

In the 20th anniversary edition of The Mythical Man-Month, Brooks reflects that the practice of field testing "beta" versions of software products had since become common practice. But he also admits that the industry’s embrace of iterative and incremental development practices has proven to be a better solution than his proposed pilot system approach.

Embracing change

Nevertheless, what Brooks did get right was the need to plan for systems to change.

Brooks observes that the role of computer programmers is to satisfy a need rather than to deliver a tangible product, and that “both the actual need and the user’s perception of that need will change as programs are built, tested, and used.”

Brooks writes that, for hardware products like cars and computers, the existence of a tangible object “serves to contain and quantize user demand for changes”. But “both the tractability and the invisibility of the software product expose its builders to perceptual changes in requirements.”

Thus it is the very nature of software, as an inherently soft and malleable product category, that requirements continually change – not only during the initial construction of the product, but also throughout its subsequent lifespan.

The only constant is change itself.

Embracing change is, of course, fundamental to genuinely-agile development practices such as Extreme Programming. But in 1975 this was quite a novel way of looking at software delivery.

Perhaps the most perceptive observation is that software development techniques themselves are subject to change over time. How we make software in one decade may look very different the next. In 2025, when AI-generated code is at the peak of the early-adopter hype cycle, this view feels prescient.

Organizational change

If we are to embrace change in our software products, there are two things we must do, Brooks writes. First, we must design our software systems to be able to accommodate changing requirements as easily as possible. Second, we must prepare the organization itself for change.

It turns out, designing software for change is the easy part. And with many new programming techniques emerging in the 1970s – things like structured programming, new high-level programming languages, compile-time operations to validate code, better modularization and sub-routining, and self-documenting techniques – it was already getting easier to design software to be easily changed after its initial construction. (Automated testing is not mentioned.)

Designing an organization for change is the hard part, Brooks observes.

To facilitate changing requirements, an organization needs to learn to treat plans, milestones, and schedules as tentative. But this is anathema to many project managers, who view slippage of delivery plans as a “failure of project management”.

Brooks proposes that his surgical team model is “the long-run answer to the problem of the flexible organization.” He explains: “it becomes relatively easy to reassign a whole surgical team to a different programming task” as-and-when necessary.

Brooks says that flat organizational structures may help to facilitate change, too. He gives the example of Bell Labs that abolished job titles and hierarchies, such that everyone was an equal “member of the technical staff”. Beyond this, “management structures also need to change as the system changes”.

This is perhaps where the agile movement of the early 2000s failed. The agile manifesto espoused the value of “embracing change” but did not prescribe how organizations themselves would need to change to make this possible. But that’s a topic for a future blog post!

Maintenance

Brooks moves on to the subject of software maintenance, which he defines as a distinct phase from software development in that the work consists chiefly of the incremental addition of new features requested by users, repairing defects in the design, and adapting the software for use in new environments and alternative configurations.

Maintenance may account for as much as 40% of the overall cost of a shrink-wrapped software product, with the final maintenance bill being strongly correlated with the number of users of the software. The more users there are, the more bugs will be found and the more features will be demanded, and therefore maintenance costs will be higher.

Citing research, Brooks shows there’s a drop-and-climb curve in bugs discovered over a product’s life. The bug rate drops off after the initial release, but then starts to gradually climb again. Brooks hypothesizes that this may be due to users fully exercising the new capabilities of the software. As users become more familiar with the software, they become more confident to try different things, and so edge case bugs start to be shaken out.

Furthermore, fixing a defect has a substantial chance – 20% to 50% – of introducing another defect. To counteract this, Brooks says that after each fix the entire bank of test cases must be re-run against the system. Today we call this regression testing and we automate it.

Methods of designing programs so as to eliminate, or at least illuminate, side effects can have an immense payoff in maintenance costs.

Brooks observes that system entropy increases over time. This is a far-reaching consequence of doing “piecemeal repairs” over extended periods. He cites studies that show that “all repairs tend to destroy structure to increase the entropy and disorder of the system. […] As time passes, the system becomes less and less well-ordered. Sooner or later, the fixing ceases to gain any ground. Each forward step is matched by a backward one. Although in principle usable forever, the system has worn out as a base for progress.”

Eventually, a system may degrade into “unfixable chaos” and a “brand-new, from-the-ground-up redesign is necessary.”

Always one for a good analogy, Brooks quotes CS Lewis:

Terrific energy is expanded – civilizations are built up – excellent institutions devised; but each time something goes wrong. Some fatal flaw always brings the selfish and cruel people to the top, and then it all slides back into misery and ruin.

– CS Lewis

Brooks concludes: “Program maintenance is an entropy-increasing process, and even its most skillful execution only delays the subsidence of the system into unfixable obsolescence.”

Communication

Throughout The Mythical Man-Month, Brooks makes various cases for communication being one of the most important skills in software development.

In chapter seven, titled “Why did the Tower of Babel fail?”, Brooks uses the biblical story of the Tower of Babel as a metaphor for the communication breakdowns that can occur in large-scale software projects. The Tower of Babel is a myth from the Book of Genesis that is meant to explain the existence of different languages and cultures around the world. According to the story, a united human race with a common language agree to build a great city with a mighty tower. Noticing humanity’s power in unity through a common language, God confounds their speech so that the people can no longer communicate effectively with one another. The people fail to complete the engineering work, and scatter around the Earth, leaving Babel unfinished.

Brooks calls the Tower of Babel “the first engineering fiasco”. But it was not to be the last. The Tower of Babel failed, like many subsequent engineering projects, not for lack of manpower, materials, time, or knowledge, but because the collaborators failed to communicate effectively with one another, and therefore they could not efficiently coordinate their individual efforts.

Communication and its consequent, organization, are critical for success. The techniques of communication and organization demand from the manager much thought and as much experienced competence as the software technology itself.

Artifacts to support communication

Brooks proposes that all communication be centered on a project workbook, a “centralized, up-to-date, and universally accessible repository of all of the project’s documentation, including objectives, interface specifications, technical/internal specifications, technical standards, and administrative memoranda.” Critically, the workbook must also record the changes made to the project over time.

Brooks goes into some length about how the OS/360 project soon ended up with a printed workbook five-inches thick, with hundreds of pages being reprinted and replaced in a typical day. The project switched to using microfiche, which reduced the costs of maintaining the workbook by eliminating the cost of reprinting large numbers of copies of the whole workbook at regular intervals. But even in 1975, Brooks noted that a “shared electronic notebook” would be a much more effective, cheaper, and simpler mechanism – and it might even be the future!

For the reasons given in the earlier chapters, the communication patterns between the architects and the programmers are the most critical to achieving successful delivery of software projects. Which artifacts can best support this communication?

Brooks asks: “how does one keep the architects from drifting off into the blue with unimplementable or costly specifications?” And: “How does one ensure that every trifling detail of an architectural specification gets communicated to the implementer, properly understood by him, and accurately incorporated into the product?”

To answer this, in chapter six, Brooks draws on a communication system worked out for the System/360 design effort. This was a hardware project – OS/360 was the operating system that ran on it – but Brooks says the techniques are equally applicable to software projects. He writes that there are two critical artifacts that need to be maintained to support communication between architects and builders:

- The manual: A external specification for the system, ie. a user manual, written by the architects. “It describes and prescribes every detail of what the user sees” and omits all the implementation details that the user does not see and which are left to the builders to decide. Feedback from users and implementers helps to refine the user interface, as it is described in the user manual.

- Formal definitions: Formal interface definitions should be used to specify a system’s internal interfaces. Formal notations are precise and complete, but lack comprehensibility, therefore good system documentation will consist of a mix of formal notations (for precision) and prose (for extra definition and comprehensibility).

Brooks expands on the importance of the user manual in chapter 15, titled “The Other Face”. Brooks viewed the user documentation as of equal importance as the real user interface to a program. He advocates that critical user-facing documentation be drafted long before a program is even built, as it serves to embody the specification of the desired user interface.

As for the “formal definition” of a program, Brooks notes that a reference implementation – which may be just a “simulation” of the intended product – can fulfil this role. Today, we might develop prototypes and proof-of-concepts to serve as reference implementations. This has a number of advantages, not least prototypes can help flesh-out requirements that can only be discovered through implementation – resource requirements and performance trade-offs, for example.

Brooks notes that newer “self-documenting techniques”, supported by high-level programming languages, can help to reduce the need to maintain comprehensive formal definitions separate from the code itself. The challenge with traditional formal definitions, Brooks observes, is keeping the definition synchronized with the program itself. “The solution, I think, is to merge the files, to incorporate the documentation in the source program.”

Besides the user manual and interface definitions, Brooks makes a strong case for product testing as a critical mode of communication between architects and builders. The role of the tester, ultimately, is to find “where the design decisions were not properly understood or accurately implemented”.

Intriguingly, Brooks suggests that testing ought to be done “early and simultaneously” with design. In chapter 13, titled “The Whole and the Parts”, Brooks observes that “many, many failures concern exactly those aspects that were never quite specified.” For this reason, Brooks says that “long before the code exists, the specification must be handed to an outside testing group to be scrutinized for completeness and clarity.” Today, we know this to be about “shifting left”, which means to move key quality and risk-reduction activities earlier in the development lifecycle.

Brooks also advocates that product testing is best delegated to an external body, rather than being done internally by the same organization that built the product. This independent product testing organization is responsible for checking the system against its requirements specifications, and serving as a devil’s advocate, pinpointing every conceivable defect and discrepancy in the final delivered product. “Every development organization needs such an independent technical auditing group to keep it honest.”

In the last analysis the customer is the independent auditor. In the merciless light of real use, every flaw will show. The product-testing group then is the surrogate customer, specialized for finding flaws.

Other important methods of communication, Brooks writes, include telephone logs, meeting minutes, and annual "supreme court sessions", typically lasting a couple of weeks, in which major architectural decisions are resolved, and prior decisions reviewed. This sounds very much like an Architectural Review Board and other such centralized decision-making processes, which have largely fallen out of favor in our industry. Decentralization of decision-making has proven to be more effective, especially at scale.

Sharp tools

“A good workman is known by his tools”, Brooks writes in chapter 12. “Each master mechanic has his own personal set [of tools], collected over a lifetime and carefully locked and guarded – the visible evidence of personal skills.” These tools could be “little editors, sorts, binary dumps, disk space utilities, etc.”

But Brooks says this is undesirable. In computer programming projects, where “the essential problem is communication, […] individualized tools hamper rather than aid communication.” Brooks continues, “it is obviously much more efficient to have common development and maintenance of general-purpose programming tools.”

He advocates there be “one toolmaker per team… [who] masters all the common tools and is able to instruct… in their use. He also builds the specialized tools his boss needs.”

The rest of the chapter looks at the categories of tools that Brooks recommends be standardized in all teams. Brooks is particularly strong in his advocacy for greater use of high-level programming languages and interactive debugging – tools that were in their infancy in 1975 and had not been available for the OS/350 development effort just a decade earlier.

The most important tools for system programming today are two that were not used in OS/360 development almost a decade ago. They are still not widely used [in 1975], but all evidence points to their power and applicability. They are (1) high-level language and (2) interactive programming. I am convinced that only inertia and sloth prevent the universal adoption of these tools; the technical difficulties are no longer valid excuses.

The combination of high-level language plus interactive programming makes for “a pair of sharp tools indeed”, Brooks concludes.

Interestingly, The Mythical Man-Month is relatively light on the topic of testing techniques. Automated testing is not mentioned anywhere. In chapter 13, “The Whole and the Parts”, there is a nod toward integration testing – “using the pieces to test each other” – but Brooks seems to be in favour of focusing on manual system testing, so as to reduce the effort required to prepare all the scaffolding needed for component and integration tests. At the time, innovations in testing techniques were focused on improvements to debugging tools, with “great leaps forward in approaches to debugging programs” with the advent of interactive debugging (ie. step-throughs and breakpoints) in the 20 years since the initial publication of the book.

Brooks writes of the importance of clearly documenting and versioning changes, with individual programmers working on “playpen” copies of the codebase. With version control systems now ubiquitous in all software development toolchains, these practices are now the norm. It is incredible to think that 50 years ago such practices were exceptional.

Today, of course, we need not spend nearly so much time and effort thinking about our tooling. This chapter provides an interesting step back in time to when every aspect of software delivery had to be carefully considered and invested in. So much is now just readily available, often freely or on a low-cost subscription.

Performance

The ninth chapter, obscurely titled “Ten Pounds in a Five-Pound Sack”, is all about using hardware resources efficiently. Much of this is no longer relevant to most types of software system developed today. Indeed, in a retrospective chapter in the 20th anniversary edition of The Mythical Man-Month, Brooks acknowledges that memory consumption limits had already been obsoleted, first by virtual memory and then by cheap real memory. By 1995, most computer users could buy enough real memory to hold all the code for all the major applications they run on their systems.

We take this for granted today – that we can run as many applications, or load as many browser tabs, as we like. Nevertheless, there are still things we can learn from Brooks’s 1975 analysis, if we are serious about optimizing our software for performance.

For example, Brooks says that size budgets should be tied to functions, such that each operation of a system must operate withing well-defined constraints – not only memory size, but also disk accesses, storage space, and so on.

Brooks also writes that, on large-scale software projects, individual teams tend to optimize for the performance targets of their own subsystems, rather than think about the total effect on the user. This may no longer be true of most monolithic systems, but it is certainly true of modern distributed systems like microservices.

And Brooks writes that the best-performing systems – those that are genuinely lean and fast – peform well because of strategic innovations, such as well-designed algorithms, rather than tactical cleverness. And the greatest performance optimizations can usually be found in the strategic design of data. Redoing the representation of data will often yield bigger performance improvements than optimizing the business logic, Brooks observes.

Representation is the essence of programming.

Still true.

No silver bullet

The 20th anniversary edition of The Mythical Man-Month adds a reprint of Brooks’s classic 1986 paper “No Silver Bullet – Essence and Accidents of Software Engineering”, plus a retrospective chapter.

The concept of the silver bullet comes from European folklore, where silver was believed to be the only material capable of killing supernatural creatures like werewolves, vampires, and witches. Over time, it evolved into a metaphor for a simple, miraculous solution to a complex problem.

The central argument in Brooks’s paper is that there will never be any more silver bullets to fight the core challenge of software development: the management of complexity. And therefore there will never be any more orders-of-magnitude increases in the productivity of software development.

“There is no single development, in either technology or management technique, which by itself promises even one order of magnitude [tenfold] improvement within a decade in productivity, in reliability, in simplicity.” Brooks continues: “we cannot expect ever to see two-fold gains every two years” in software development, as there is in hardware development. In other words, there will never be an equivalent in software development of Moore’s Law.

To explain why, Brooks distinguishes between two different types of complexity in software: accidental complexity and essential complexity. This is, perhaps, Brooks’s most famous and enduring idea.

Brooks’s philosophy of software complexity is adapted from Aristotle. In Aristotelian philosophy, essential properties are the properties that make something what it fundamentally is – its essence. Remove them and the thing ceases to be that thing. Accidental properties are qualities that a thing happens to have, as if by accident. These properties can be removed without fundamentally changing the nature of the thing.

Applied to software, essential complexity is found in the aspects of a system design that are essential to solving the problem that the system is intended to solve. Essential complexity is derived from the problem domain: the concepts, relationships, and logic that must be expressed in order to fulfil the requirements of the user, and to apply the business rules and meet real-world constraints. Nothing can be done to eliminate this form of complexity.

Accidental complexity, on the other hand, arises from our choices of tools, languages, syntax, data structures, and logic to solve the problem. Accidental complexity cannot be eliminated entirely, but it can be minimized by making good trade-offs in our software designs.

Brooks’s argument is that most of the challenges in software development arise from software’s essential complexity, not its accidental complexity. It is the nature of software systems that they are “more complex than most things people build”. Software systems have a large number of possible states, which makes conceiving, describing, and testing them very hard to do. And, unlike physical products, scaling up is not a matter of producing more of the same thing, but it concerns designing, constructing, and testing entirely new and original components and having them interact seamlessly with existing components. Software, uniquely, “is constantly subject to pressures for change”. Most software is continuously iterated, rather than updated versions being entirely new.

Many of the classical problems of developing software products derive from this essential complexity and its nonlinear increases with size. From the complexity comes the difficulty of communications among team members, which leads to product flaws, cost overruns, schedule delays. From the complexity comes the difficulty of enumerating, much less understanding, all the possible states of the program, and from that comes the unreliability. From the complexity of the functions comes the difficulty of invoking those functions, which makes programs hard to use. From complexity of structure comes the difficulty of extending programs to new functions without creating side effects. From complexity of structure comes the unvisualized states that constitute security trapdoors.

All the difficulties in the management of software projects arise from the inherent characteristics of software itself. Thus “the complexity of software is an essential property, not an accidental one.”

“If this is true,” Brooks concludes, then “building software will always be hard. There is inherently no silver bullet.”

Brooks believed that a series of innovations attacking essential complexity could lead to significant further improvements in developer productivity. Brooks considered innovations such as incremental development practices, techniques for rapid prototyping, and the emergence of a mass market for software components (allowing us to buy, rather than build, the software we need). All of this innovation had attacked the essential complexity of software development, leading to worthwhile improvements in productivity. But, Brooks concluded, none of them proved to be silver bullets.

At least we can work to improve the accidental complexity of our software systems. Alas, Brooks also believed there had already been sufficient technological advances to reduce most forms of accidental complexity as much as it ever could be. By 1986, the advent of high-level programming languages – which Brooks suggested had increased programming productivity as much as five-fold – had already all-but eliminated accidental complexity from computer program code. Meanwhile time-sharing and integrated programming environments had greatly simplified the software development process itself.

Brooks looked ahead to recent advances in high-level programming languages such as Ada, to improvements in programming environments and tools, to the hope for object-oriented programming and tools for program verification at compilation time, and indeed to the promises of artificial intelligence and other forms of “automatic programming”. In all cases, Brooks argued that the productivity gains from each of these advances would be merely marginal.

Was Brooks right?

In the intervening decades, there have certainly been many further important innovations attacking both the essential and accidental complexity of our software systems. For essential complexity I would argue that techniques in domain modeling and domain-driven design patterns have been very helpful. As for sources of accidental complexity, the success of open source, free and low-cost tools and languages, version control systems, virtualization/containerization and cloud computing, continuous integration and automated deployment pipelines, and – most recently – AI-augmented programming, have all incrementally transformed how we build software.

But there is an ironic consequence of these innovations: the productivity gains from them have been offset by corresponding increases in demand for what software is required to do.

Throughout the history of computing, advances in technology have helped to make us more productive. We can build software faster, to a higher quality, and at far larger scale, than ever before. But the same advances have also created opportunities for ever more ambitious software.

Today, the resources and tools at our disposal are as powerful as they have ever been. But the productivity gains afforded by these tools are offset by corresponding increases in the essential complexity of the software that we are commissioned to make on behalf of our customers.

Brooks eludes to this in the original 1975 epilogue to The Mythical Man-Month:

The tar pit of software engineering will continue to be sticky for a long time to come. One can expect the human race to continue attempting systems just within or just beyond our reach; and software systems are perhaps the most intricate and complex of man’s handiworks. The management of this complex craft will demand our best use of new languages and systems, our best adaptation of proven engineering management methods, liberal doses of common sense, and a God-given humility to recognize our fallibility and limitations.

Concluding thoughts

The Mythical Man-Month is the book that everyone claims to have read, but few have. I would encourage everyone to do so. It’s a wonderfully imaginative book, rich in metaphor and analogy, and filled with pearls of wisdom. It’s a must-read for anyone working in the software industry. The 20th anniversary edition is recommended for its extended content.

What I learnt from The Mythical Man-Month is that modern best practices in software development are deeply rooted. The seeds for our current ways of working were sown here, in the 1960s and 1970s, when we started to push the boundaries of what software could do. Almost all of the ideas put forward by Fred Brooks in this book are just as relevant in 2025 as they were in 1975.

Of course, some of the challenges today are different from what they were in the time of OS/360. Notably, we are no longer physically constrained by computing resources. Hardware is abundant, easily sourced, and cheap. Yet physical constraints remain for many categories of software – real-time systems, embedded systems, safety-critical systems, and many other systems operating in domains that have strict performance requirements.

Yet, for all our advances in technology and working practices, in 2025 the core challenge of software development remains the same as it ever has been: the management of complexity.

And perhaps this will always be the challenge.

In a closing retrospective chapter printed in the 20th anniversary edition of The Mythical Man-Month, Brooks reflects on reasons for the book’s success and popularity. Among numerous explanations that Brooks offers, one I find to have the greatest truth. It is that “The Mythical Man-Month is only incidentally about software but primarily about how people in teams make things.”

The Mythical Man-Month will never become obsolete. Superficially, the book is about software development, which is ever-changing. But more fundamentally the book is about how people collaborate to solve complex problems. And that is a challenge for humanity that will endure across time, cultures, and technologies.